Khama Rhino Sanctuary lies just west of the A14, Botswana’s main highway connecting Serowe to Orapa. White and black rhinos take pride of place here: it’s one of the few places where they are safe. The sanctuary, a community-led project, is protected by the highly effective Botswana Defence Force (BDF). Not a single rhino has been poached in the reserve since its inception 25 years ago.

It’s unusual for the army to be involved in wildlife protection, a duty they’ve undertaken since their formation in 1977. “Poaching was a threat both to income from hunting and to [Botswana’s] growing and lucrative high-cost, low-volume tourist safari industry,” Keith Somerville explains in his book, Ivory. It helped that the BDF deputy commander and president’s son at the time, Ian Khama, was personally committed to conservation and had a financial stake in the tourism industry. The country’s strong commitment to conservation continues to explain Botswana’s conservation success story, which is something of an anomaly in the region.

I happen to have grown up nearby but we had left Botswana by the time the reserve was established in 1992. In 2014 I visited the sanctuary for the first time while on a field research trip. A ranger looked sceptically at my hired sedan, cautioning that only SUVs were allowed. I convinced him it would be alright; besides, I had already paid the entrance fee. In the end, I had to be towed out of the mud.

Though it’s a small reserve (8 585 hectares), the wildlife experience is comparable to other small parks such as Addo Elephant Park in South Africa. In that idyllic setting, watching rhinos carry their dinosaur skin and iconic horns, it was hard to imagine that this majestic species was at risk of extinction in our lifetime.

While Botswana is a wildlife haven, its neighbours South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe are battling an escalation in rhino poaching. This regional crisis will require regional co-operation to achieve conservation success. Much of the focus is currently on South Africa, where heated debate around legalising rhino horn trade has dominated the news.

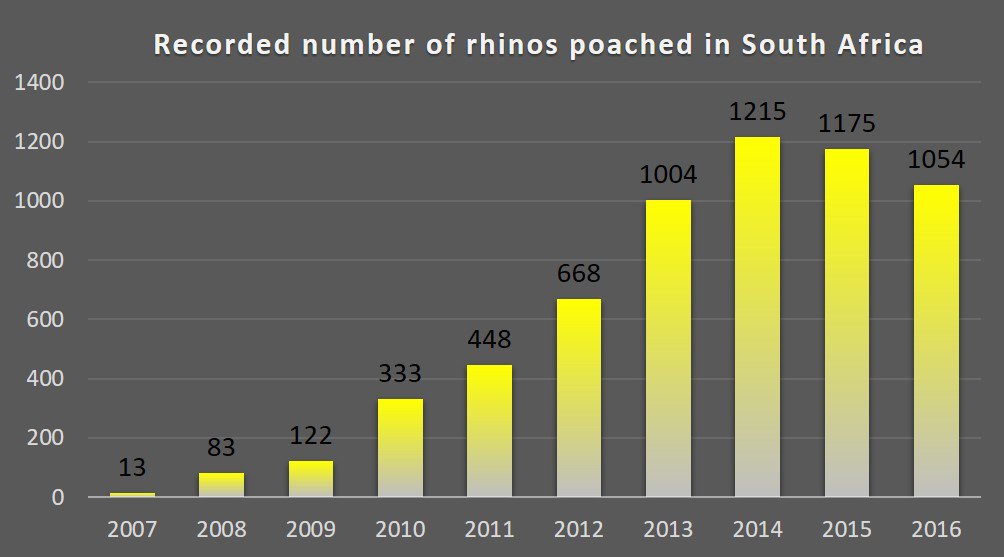

At the current rate of poaching, rhinos will disappear in less than 20 years. South Africa is home to about 75% of the world’s remaining rhinos: it hosts roughly 18 000 white rhinos and 4 000 black rhinos. If South Africa continues to lose over 1 000 a year (as has been occurring since 2013), the outlook for rhino survival is bleak.

Most poaching happens in the Kruger National Park, one of the largest game reserves in Africa, which is situated in the Limpopo province. As rhino populations there decline and poaching becomes more difficult (due in part to militarised responses and successes in rooting out internal corruption), poachers have started to target parks in the Kwa-Zulu Natal province.

View our interactive timeline on the decline of rhinos in South Africa here

As part of its conservation efforts, South Africa is trying to translocate as many rhino as possible to secret locations in Botswana.

Botswana is a sanctuary for rhinos and elephants in a region that is experiencing a poaching crisis. The country’s law enforcement and anti-poaching strategies are more effective than South Africa’s. A 2017 report by the Institute for Security Studies finds that Botswana’s ‘militarised responses effectively reduce poaching’ through a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy. The authors note the moral reservations of such a policy but forcefully argue that its deterrent effect accounts for Botswana’s relative success in the region, given that most other anti-poaching techniques are highly similar.

Like rhinos, Africa’s elephants are under grave threat. The number of African elephants has fallen by around 111 000 to 415 000 in the past decade, the worst drop in 25 years, according to the latest report from the IUCN. Roughly 20 000 elephants are being poached in Africa each year.

According to the Great Elephant Census, for instance, there are roughly 130 000 elephants in Botswana, nearly a third of the continent’s remaining savannah elephants. Many have migrated there from neighbouring countries – “elephant refugees” – to escape hunting or poaching. Some have argued that this has the unintended effect of elephant overpopulation in Botswana but this is disputed in conservation circles. It does seem to hold, though, that an over-concentration of elephants in too small an area can damage ecosystems, and increase human-wildlife conflict.

Hunting ban conundrum

On a follow-up trip to the Okavango Delta and Chobe National Park in September 2015, my colleague Romy Chevallier and I had a fascinating conversation with a senior adviser to the Botswana government and a leading ecological consultant. Two things he said should cause us sleepless nights.

First, “The greatest threat to tourism [in the Okavango Delta] is tourists.”

This sensitive wilderness landscape has a limited carrying capacity . In other words, the environment can only sustain a limited number of tourists, as tourists have an impact on the land and its resources through waste generation and pollution .

Tourism is an excellent source of ‘non-consumptive sustainable use’ revenue that helps to conserve rhinos. But if you undermine the ecology on which tourism attractiveness is built, you can destroy both. It must be carefully managed.

Tourists, especially photographic tourists, leave a particularly large carbon and waste footprint. Photographic safaris require a large bed-night capacity and more days than a hunting safari. The lodges in the Delta are difficult to access. Guests have to be flown in. Supplies have to be brought in by plane or by boat. Hunting tourists do not require the same level of resources. The Delta itself is much more ecologically sensitive, for instance, than the Kruger Park in South Africa, which is hardier. This is because the entire ecosystem is delicately predicated on a narrow hydrological margin. In other words, if upstream water flows are negatively affected, the Delta is at risk of drying up.

Second, talking about Botswana’s decision

to ban all trophy hunting, the adviser said: “I understand why locals poach for

bush meat. In the absence of hunting revenue, which also provided meat for

local communities, I might also poach instead of serving at the white man’s

table on photographic safaris.” Illegal bush meat hunting is indeed on the rise

and poses a serious conservation threat, especially in the Delta.

At the time, tempers were flaring over whether the hunting ban would inadvertently lead to more wildlife poaching. When we visited one of the community trusts near Chobe National Park in September 2015, one of their senior board members quipped, “Secret location? We know that secret location and we will poach those rhinos.”

This was an expression of resentment towards the ban, which they claimed had resulted in an overnight halving of revenue for the community trust. Whether rhinos would be specifically targeted is arguably not the point; what matters is that at least some communities appeared to have justified poaching to themselves.

Such conversations are rife with the complexities of rhino conservation and wilderness landscape preservation more generally. The latter is crucial, as poaching is a severe, but arguably not the primary, threat to species like elephants and rhinos. Habitat contraction and fragmentation – the process of protected wilderness landscapes being degraded, cleared or split up for alternative economic activities – are more serious long-term challenges. To ensure survival of large mammals such as elephants and rhinos, the poaching and law-enforcement problems must be solved alongside the habitat problems.

To legalise rhino horn or not: the big debate

Our 2015 field research trip to Botswana came about six months after the public rhino horn hearings in Johannesburg. A committee of inquiry had been established by South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) into the possibility of promoting a legal trade in rhino horn ahead of the 17th Conference of the Parties (CoP17) for the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). That meeting took place in September 2016. By then, the South African authorities had been convinced by the committee of inquiry’s findings not to promote an international trade in rhino horn.

An international ban has been in place since 1977, and it would have taken a two thirds majority of CITES members to overturn the status quo. The DEA appears to have taken this decision to avoid international humiliation, and for strategic reasons – South Africa’s political capital would have been undermined by lobbying for motions that have limited probability of success. In the end, Swaziland submitted a motion to CoP17 to introduce a limited, regulated rhino horn trade. While South Africa, along with Namibia, supported Swaziland’s bid, it chose not to submit one itself.

Both the 2015 hearings and the 2016 CoP17 meetings were inflammatory affairs. Proponents and opponents of rhino horn trade – as a potential conservation strategy – hold deeply cemented views. They spoke at and past each other, rather than with each other. The polarised polemics obfuscate some of the other complexities and dilute the collective action required to defeat the criminal syndicates at the centre of the problem.

The binary nature of the debate also tends to overlook the importance of frontline communities as potential drivers of conservation. Communities who live near parks that try to protect rhinos should be at the centre of our conservation strategies. This is difficult to achieve in practice though, because where conservationists land on the trade question has a profound influence on how they think communities should benefit. Trade proponents argue that communities should be recipients of revenue raised from selling rhino horn in legal markets. Opponents argue that no public money is effectively ring-fenced, and communities should rather become partners in tourism initiatives. More importantly, if the horn-sale strategy backfires, communities will be left with no rhinos in the parks near them, and no opportunity to derive future revenue from tourism.

Philosophically, the debate is characterised by those who see the ‘sustainable use’ doctrine – which influences wildlife policy formation – as tantamount to placing a monetary value on an animal’s head so that it can ‘pay its way’, and those who see it as a broader concept integral to biodiversity conservation through non-consumptive use.

How the rhino poaching crisis began

As Keith Somerville notes in Ivory, this question of rhino and other large mammal conservation is deeply embedded in the political economy of Africa’s development. Hunters of European origin started to destroy elephant and rhino populations in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and ivory financed the colonial endeavour more than is commonly recognised. It effectively subsidised settlement. When these hunters started to recognise that the practice was unsustainable, many of them became conservationists. But many, hypocritically, did not refrain from hunting themselves. Instead, they constructed a discourse that painted indigenous people groups as ‘poachers’ and themselves as ‘conservation-hunters’.

This discourse – white hunters/black poachers – became the driving rationale behind building national parks and game reserves. Thousands of local communities were permanently displaced through the creation of parks or what the literature calls ‘fortress conservation.’ An important legacy effect resulted. Communities felt betrayed by their governments, and the consequent resentment towards wildlife meant that poaching became an attractive livelihoods option, especially for those who were denied access to land from which they’d sustainably secured food for generations. Moreover, the historical use of ivory as a form of elite wealth accumulation helped to plant the seeds of predatory accumulation and patronage systems that persist today despite it being evidently myopic and unsustainable.

By 1895, there were fewer than 50 white rhinos left in South Africa. A variety of conservation efforts, including incentives for private game ownership, saw that number slowly improve. By 1968, numbers had recovered to about 1 800. While a notable recovery of white rhinos had started in South Africa, global rhino numbers continued to plummet.

In response to the global poaching crisis, CITES members decided in 1977 to ban the international trade in rhino horn. This ban, and subsequent attempts to ban illegal wildlife trade more generally, have been characterised as an extension of colonial attitudes to conservation. The view is probably not entirely fair, as many who recognise the depravities of the past are nonetheless in favour of trade bans as the best means by which to conserve wildlife.

By 1994, South Africa’s white rhino numbers had recovered to the point where CITES countries accepted a motion to downgrade them to Appendix II. The CITES listing system is important to understand here. Appendix I-listed species cannot be internationally traded at all, except for scientific reasons (which remains a major loophole, as only the importing scientific authority needs to deem it ‘scientific’ for it to be allowed). Appendix II allows limited trade in species and their products – the export of horns obtained in non-commercial, personal trophy hunts.

While South Africa’s rhino numbers grew into the early 2000s, numbers elsewhere continued to fall, replicating the scenario in the late 1960s. Proponents of a legalised international trade in rhino horn point to South Africa’s conservation successes as a model for ‘sustainable use’, which should be replicated elsewhere. But this argument faces several challenges. In 2003, as a National Geographic timeline explains, “Asian nationals began exploiting CITES’s downgrade of white rhinos by obtaining licenses to export trophy horns and then selling them on the black market.”

The corresponding demand-side component – ultimately the most important variable to understand – to the chronology is that in 2006, several factors combined to create unprecedented demand for rhino horn. Many sources attribute the genesis of the boom to a former Vietnamese politician allegedly testifying to ground horn as the cure to his cancer. Income per capita was also increasing, and rhino horn was demanded as a prestige item in both Vietnam and China. High-level government officials were among the most high-paying consumers.

Demand has since evolved into highly differentiated products, from shavings and powder to bangles and libation bowls. The most frightening recent practice is to drink tiger-bone wine from a rhino-horn wine glass. On the demand front, the yearning for ever more exotic products in Asia is fuelling wildlife slaughter in Africa.

In 2007, poachers killed 13 rhinos in South Africa, the entire national amount for the previous 17 years. It was the beginning of a new crisis that escalated rapidly. The next year, the number of poached rhino spiked to 72. One could argue that this was minimal in comparison to the size of the population, which had by then grown to about 15 000 – still a remarkable conservation success story. But in February 2009, police bust a criminal syndicate trying to traffic 50 horns out of the Kruger National Park. This signalled an entirely different problem – the involvement of transnational organised crime in the rhino game. Given that a significant portion of demand was coming from politicians or politically-connected consumer elites in Asia, it wasn’t a stretch to connect the dots that they at least helped to facilitate the illegal importation of tons of horn. DEA’s response to the renewed crisis, in June of the same year, was to impose a moratorium on the domestic rhino horn trade.

Legal battle

Three years later, in 2012, Johan Krüger – a South African game farmer – sued the government for what he considered to be an unconstitutional imposition on his right to profit from private property. Breeding rhino privately to provide a stable supply of horn to market seemed a viable approach. Poaching had increased to over 1 000 rhinos a year by this stage. Many believed that the international and domestic bans had failed. Out of desperation, they were willing to support the trade experiment.

In July 2013, the South African government announced that it planned to promote a legalised international rhino horn trade at the 2016 CITES CoP17 meeting, which it was to host. The move proved highly controversial, with conservationists criticising the process as lacking in transparency and sufficient public consultation. Some suspected that the government had been unduly swayed by the well organised Private Rhino Owners Association (PROA).

In a strange turn of events, the government in 2014 published a study which concluded that the moratorium should remain in place. On the one hand, it appeared amenable to the likes of the PROA. On the other, it appeared weary of upsetting global sentiment. In hindsight, there may also have been a strategic decision to sacrifice the rhino horn trade proposition in exchange for more support of its ivory trade proposals (to remove the limitations on trading Appendix II elephants and their products).

John Hume, the world’s most successful rhino breeder, joined Krüger’s lawsuit in 2015. A National Geographic article at the time put it this way: “Hume and Krüger contend that rhino horn is a renewable resource, since a horn can be painlessly cut off. And they say that a legal domestic trade in horn would depress prices and discourage poaching, as well as allow proceeds to go toward conservation. They also favour lifting the international ban.”

In September 2015, the case went to court. The pair argued that it is their constitutional right to sell horn, as Section 25 of the Constitution protects private property rights and allows property owners to dispose of their property as they see fit.

Private game ownership has clearly played a significant role in the protection of South Africa’s wildlife. By 2015, white rhino numbers were up to 18 613, with a full 6 141 of those under private management. The remaining 12 472 are under state management in national reserves. Conservation success through private ownership, however, is not an automatic argument in favour of a legalised trade. Domestic trade has not been permitted since 2009. And while overall rhino numbers have dropped since then due to the poaching epidemic, private breeding has continued despite high security costs and not being able to trade horn.

Private rhino owners argued, nonetheless, at the DEA-hosted 2015 public hearings of the committee of inquiry into a possible legal rhino horn trade, that – in addition to private property rights protection – the Constitution supported the doctrine of ‘sustainable use’.

Section 24 (b) (iii) states: ‘Everyone has the right to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures that… secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development.’ On a narrow reading, this view contends that a renewable resource such as rhino horn can and should be sold on the open market. Its sale, goes the argument, helps to fund conservation.

A discourse of ‘if it pays, it stays’ has come to characterise this narrow reading. Because of the substantial costs associated with protecting rhinos, private owners argue that rhinos must pay their way through the sale of horn to consumers. A more contextual understanding of ‘sustainable use’ recognises that non-consumptive use may do more to conserve the species and its associated habitat biodiversity. This is especially the case if consumptive use doctrine backfires, and a legal domestic trade in rhino horn inadvertently fuels illegal consumption in Asian markets.

In April 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled – on procedural grounds – that the moratorium be overturned, as the DEA had not followed the correct procedures back in 2009 in implementing it. Had it made a substantive ruling, more clarity would have been brought to bear on this murky issue.

In August 2017, a South African court ordered the government to release a permit to John Hume to allow him to host a 3-day online auction of his stockpiled rhino horn to local buyers. Hume owns 1 500 rhinos and claims that security for his herd costs about $170 000/month. He had been granted a permit previously, but it was withdrawn by DEA, which precipitated more court action by Hume to have it reinstated.

This reversal of DEA’s position and the effective creation of a domestic market has invigorated support for commercial farming of rhino horn. But breeders’ arguments that a legal market will protect wild populations ignore how the illicit trade in wildlife products functions. Poaching levels are chronically high, but it does not follow that the only solution is to resort to legalising the domestic trade, especially while an international ban remains in place.

Problems with the pro-trade argument

Hume’s primary argument is that “the demand for rhino horn is high and open trading of the horn has the potential to satisfy this demand to prevent rhino poaching.” Opponents of the trade argue that it is at best unclear what will happen to demand for horn if trade is legalised. The risk is that currently dormant demand will be re-ignited, shifting the demand curve outwards, possibly fuelling more poaching. A legal trade signals that consumption is legitimate, which would immediately undermine any stigma effect currently in operation. Pro-traders recognise that current demand “is not going to die down anytime soon”, but argue that because horn is a renewable resource, appropriate policy incentives to promote breeding will increase supply: “If we do not take steps to meet the demand, we won’t save the rhino”. However, this is a risky approach. We do not know what will happen to demand, and experiments are difficult to reverse.

For Hume’s argument to work, he has to demonstrate that a significant portion of demand can in fact be satisfied with legal supply, and that there is no risk of a legal supply inadvertently leading to even higher rates of poaching. It seems likely, to the contrary, that the farming of rhinos may be sustainable for narrow business purposes, but not as a means of preventing the poaching of wild rhinos. A recent academic literature review concludes that because wildlife products are often seen as a status symbol, wild animals are considered superior because of their rarity and high expense. Evidence for wild horn is normally provided by showing buyers that it has been removed from the base of the skull. The rhino cannot survive this mode of extraction, and it seems unlikely that there are conscience-stricken consumers who will only buy horn sourced from breeders such as Hume.

The literature is also clear that the demand for most wildlife products by far exceeds what commercial breeding can currently or realistically offer. Finally, a recent paper reveals that poaching effort is insensitive to changes in the retail price of rhino horn. For the price mechanism to eradicate poaching, prices must drop to very low levels. To reduce syndicates’ profit margins to the point where they cannot afford to pay poachers, demand would have to effectively disappear.

Supply-side interventions are unlikely to be effective, as a threshold price would be required to incentivise breeding. The pro-trade position tends to assume, as Hume does, that creating competition “in the form of legal trade has the potential to correct the perverse value of the horn, which is what is driving rhino poaching.” Horn sells for anywhere between $35 000 and $60 000/kg in Vietnam and China. Hume is convinced that with the correct permitting system and detection technology in place, legal horn can be identified and that law enforcement would be able to “keep illegal horn out of our legal trade route.”

This argument depends on meeting two conditions, neither of which is plausible. First, farmed supply will have to substitute for products sourced from wild animals. As indicated above, this is unlikely. Second, law enforcement officials would have to increase effort and resources towards detecting illegal supply to ensure it isn’t laundered through legal channels. This requires governments to outsmart syndicates. But syndicates currently smuggle horn in large volumes, often with the direct involvement of government officials, which suggests that such faith in governments may be misplaced.

Hume’s response to the problems expressed above is that because the status quo is failing, our only option is to experiment. He misattributes a quote to Einstein that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Aside from the fact that Einstein never said this, this is what logicians call a leap from assertion to conclusion. It follows a line of reasoning that says: ‘x (efforts to stop poaching) is not working. It is correlated with y (a trade ban). Therefore, the solution is to remove y.’ But this is a correlation/causation fallacy – confusing the existence of a trade ban alongside poaching as the cause of poaching.

As demonstrated in the timeline, the time sequence of the relationship between the ban and poaching is that the ban followed an upsurge in poaching. That suggests that a shift in the demand curve was the root cause of increased poaching. It therefore does not follow that removing the trade ban is wise policy.

A legal domestic trade in rhino horn appears to offer little conservation value for the species. Even if legally farmed supply from South Africa satisfied a portion of the demand in Asia, it would not change the demand function for consumers whose preference is for wild product or for those who are indifferent between farmed and wild horn. Neither would a legal supply be able to out-compete illegal syndicates. Their profit margins are high and they pay a flat rate to poachers. A legal trade would likely produce a parallel market with extensive laundering from illegal into legal channels. This only makes business sense for the likes of Hume; it does not make sense for trying to conserve wild rhinos. At worst, it may severely undermine conservation and demand-reduction efforts.

Not on our watch

To save the rhino, collective action is required. A consensus has to be reached that supply-side interventions are likely to be counter-productive to the objective of reducing demand. This is difficult for people who have banked on the possibility of a legal trade to compensate for sunk capital. But demand reduction campaigns are undermined by confused signalling from the supply side. The presence of a legal domestic trade in South Africa creates problems. Therefore, steps should urgently be taken to have a new moratorium reinstated that is procedurally and substantively correct. Private interests cannot dictate how a public good like the iconic rhino should be conserved.

Ultimately, this is an ethical issue as well as an economic one. Human greed to profit from rhinos is easily disguised under the conservation trope that ‘if it pays, it stays’. The truth is that the net present value of a rhino over its photographic tourism lifetime far exceeds what can be made from selling its horn in any event. And if the selling of that horn exacerbates poaching, even private interests will lose.

As I sat watching those rhinos in the Khama Rhino Sanctuary, it occurred to me that my grandchildren may not see these animals in the wild. My son had been born 11 months before my trip, and I recorded a video in which I implore him to give of himself towards the survival of this iconic species. Ultimately, we have a responsibility to steward our natural resources well, to see their survival as integral to our sense of humanity. Many feel that this is overstating the case, but it bears out again and again that our disconnection and alienation from the true, inherent value of nature has produced problems that are now potentially irreversible and cannot be solved by new technologies alone.

We all have to play a part in conservation for the sake of our own human dignity.

(Main image: Shivang Mehta / Barcroft Images / Barcroft Media via Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.