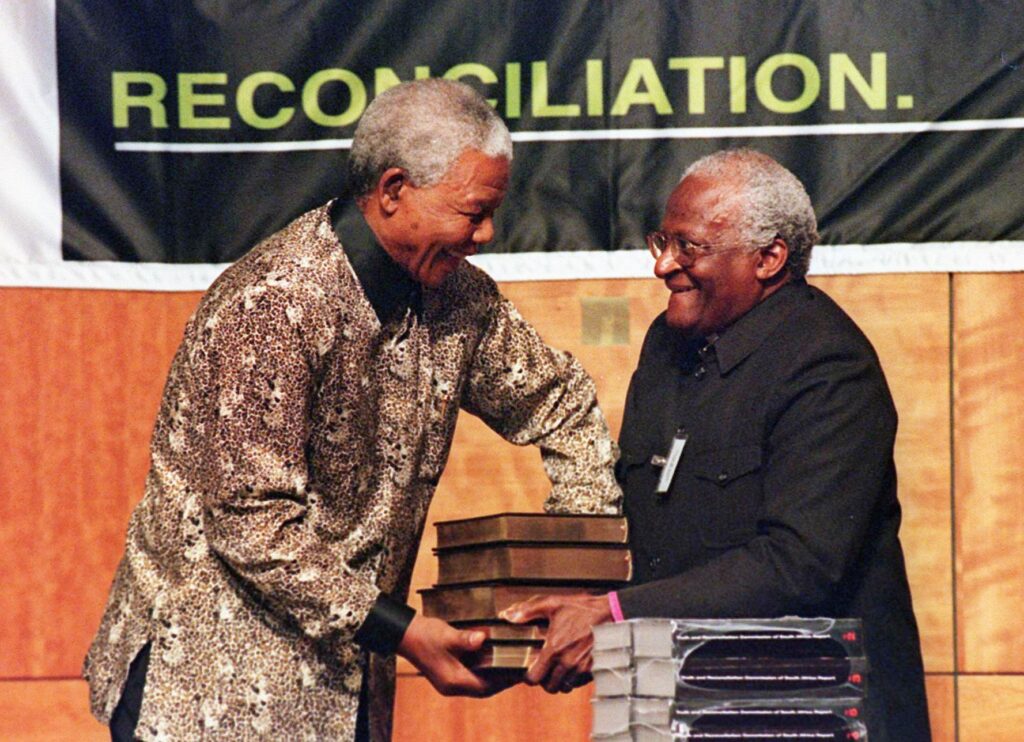

South Africa celebrates 25 years of democracy this year. Last year, it marked the 20th anniversary of the submission of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report to then-president Nelson Mandela.

These are major milestones that warrant critical reflection. South Africans are trying to move out of the dark and long shadow which the past continues to cast over our society. Many thought it would be a quick journey. There was hope that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) with its amnesty and reparations components would “enable South Africans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation” (in the words of then justice minister Dullah Omar) and that a democratically elected government would swiftly transform our society into a prosperous one. In the magnificent afterglow of the transition and the hope embodied by Mandela’s presidency, we must forgive those who let hope overshadow that which was realistic and feasible.

There is no doubt of the very significant role performed by the TRC in South Africa, and indeed on the continent as a whole. While it was by no means perfect, it remains to date the most celebrated model of a truth commission in Africa and its staff and commissioners continue to be consulted widely by countries in transition to share their experience and advice.

The purpose of this article is not to rehash the nature and successes of the TRC, but to highlight an important area that was overlooked by the commission and the post-TRC dispensation: the psycho-social impact of apartheid and its long-term impact on individuals and communities. But first, a few basic premises are worth noting: It is well known that the TRC was set up by the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act of 1995. Its mandate was “to bear witness to, record and in some cases grant amnesty to the perpetrators of crimes relating to human rights violations and to provide reparation and rehabilitation to victims”.

The chairperson, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and his vice chair, the late Alex Boraine, were appointed by Mandela. They were supported by a publicly approved team of eminent commissioners, investigators, researchers and translators, among others. Over 20 000 testimonies were heard as the commission travelled around the country, closely followed by the media, to hear the truth of how apartheid had systematically destroyed the fabric of our nation. Once-off reparations were to be paid to those formally declared as victims by the commission. Of 7 112 amnesty applications received, only 849 were granted.

South Africa’s TRC process and outcomes have been extensively discussed, written about and analysed. However, though practitioners across the world continue to warn one another that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach (incidentally the African Union’s newly adopted Transitional Justice Policy emphasises context specificity) to dealing with the past, I fear that we still too often copy and paste key elements of South Africa’s journey into and onto other contexts without critically examining contemporary local realities.

“The failure to understand, acknowledge and address the impact of the past on the psycho-social wellbeing of South Africans has been a major shortcoming in the post-TRC democratic dispensation.”

Rather, African practitioners of transitional justice ought to look at South Africa today with its growing inequality, increasing civil unrest and protest action, high levels of corruption, poor service delivery and spectacular levels of violence. They should try to understand what could have been done differently in the aftermath of the TRC to prevent the past from further damaging South Africa.

An important variable which continues to receive too little attention on the continent concerns the relationship between the field of mental health and psycho-social support on one side, and peacebuilding and transitional justice on the other. The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) was born out of the TRC process. Its focus on these fields originates from the organisation’s dialogue and reconciliation efforts in South Sudan, where it has been working to support reconciliation processes for the last 10 years. Incidentally, the failure to understand, acknowledge and address the impact of the past on the psycho-social wellbeing of South Africans has been a major shortcoming in the post-TRC democratic dispensation.

In South Africa, millions of predominantly poor black people exist between two layers of pain.

The first layer has developed as a result of the collective experience of existing for more than 400 years as second-class citizens during systems of slavery, colonialism and apartheid. While research on the inter-generational transmission of trauma in South Africa (and indeed in Africa) is still very slim, the IJR’s work in this field shows that South Africans live with, and often continue to identify as shaped by a brutal and unjust past in which they were inferior and marginalised.

Second, this historical trauma is compounded by very poor socio-economic conditions, which are still prevalent across the country. The result is what we call “daily stressors”. These result from living in relative poverty in communities characterised by high levels of unemployment (currently at 27% nationally), poor service delivery, some of the highest levels of sexual and domestic violence in the world and the ever growing phenomenon of gangsterism.

Together these levels of pain make for a toxic mix. In the words of Nicaraguan psychologist Martha Cabrera, we live in a “multiply wounded” society.

How do these matters relate to the TRC? The commission received only about 20 000 testimonies. This means that the majority of South Africans (of a population of approximately 40 million in 1995), most of whom had in some way or another experienced the wrath of the apartheid regime, never had the opportunity to share their story — to feel heard and acknowledged, to engage in the kind of dialogue necessary to begin a reconciliation journey. It is unrealistic to expect any TRC to systematically engage the psycho-social well-being of an entire nation, especially when the wounds are as deep as they are in South Africa. Had the recommendations of the TRC report been implemented more systematically, some of these issues might have been addressed. However, in the absence of this, people across South Africa use the IJR’s dialogue spaces to express feelings of hopelessness and of being forgotten, and a deep sense that their sacrifices during the struggle against apartheid were in vain.

Furthermore, researchers have found that the relationship between truth-telling and psychological healing and peace-building is doubtful. For some people, participating in truth-telling processes has positive effects. For others, the effects are negative in that they have the potential of opening psychological wounds that can result in increased depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder. Truth-telling, they argue, has no significant impact on the sense of injustice, feelings of revenge, violence and retribution, and on improvement in the psychological effects of trauma. They argue that “policy-makers need to restructure reconciliation processes in ways that reduce their negative psychological costs, while retaining their positive societal benefits”. This underscores the importance of instituting broader-reaching and longer-term processes, ideally situated in communities, to systematically talk about the past.

We know that conflict weakens the social fabric that governs relationships and the capacity for recovery. But we must understand that, in the aftermath, the causes of interpersonal conflict might still exist and may even have worsened as a result of violence during the conflict. The ability of individuals and societies to cope with such extraordinarily painful experiences, and with the developed mistrust and fear, is often impressive. However, it is also limited and the breakdown of coping strategies is frequently related to psycho-social trauma. Due to the conflict the natural ties, rules and bonds between people and within communities that strengthen coping and resilience are often destroyed.

Restoring the social fabric that binds and supports people within their own communities is vital for those who have experienced serious traumatic events. Recreating the feeling of connectedness to other people is essential for building reconciliation.

Given that conflict tends to adversely affect people’s mental health, and that high levels of poor mental health affect the ability of individuals, communities and societies to function peacefully and effectively during and after conflict, I would like to argue for us to be far more conspicuous and creative in integrating mental health and psycho-social support structures into all levels of the post-conflict justice and reconciliation journey.

Recent research by Canaletti from Israel and Palestine, for instance, shows that mental health is a key contributor to many of the underlying attitudes that perpetuate the continued cycle of hatred and aggression between Israelis and Palestinians. They argue that the dearth of available psychological support services in Gaza is not only a humanitarian problem, but also a barrier to progress towards reconciliation. As in South Africa, the rising violence in many communities emphasises the crucial need for comprehensive interventions that bolster coping, and that mitigate the loss of social and economic resources, reduce threat perceptions, and ameliorate mental disorders.

South Africa should have put in place institutions, mandated to operate long after the TRC closed its doors, to engage proactively and collectively with the citizenry in dialogue about their experiences and memories of the past. Such institutions would not only have benefited those sharing and listening but, if documented, would also have contributed to a more comprehensive and inclusive record of the past that could be taught to future generations, so many of whom have very little understanding of South Africa’s path to democracy

Ensuring a continued constructive engagement with the past — ideally through the creation of dialogue platforms on race and racial identity at micro-, meso- and macro levels — might prevent some analysts from saying things like “reconciliation in South Africa has not failed; it has simply not been attempted”; or “it is not because of too much reconciliation that justice was not realised, but because of too little”.

In South Africa, there are no long-term mechanisms and structures to ensure the continued development of projects and activities that keep the conversation about the past on the table. These would have been both a reminder of the past and what was achieved, and also served as a lodestar for the future to remind us where we don’t want to go again. They could have done a lot to prevent us from getting to the very volatile situation we are in today.

One advantage is that we know quite a bit about the nature of the challenges we face. Since 2001, the IJR has hosted the South African Reconciliation Barometer, a public opinion survey which tracks reconciliation in South Africa. This provides annual statistics for government, civil society and the population at large on how South Africans themselves feel about reconciliation, about one another, and about government and the future.

The latest round of the survey tells us that when asked how much they trust people from other race groups, 41% said somewhat, and 21% said not very much or not at all. Asked how often in the last month people interacted or talked to someone from a different race group at social gatherings and events, 46% said rarely or never. Finally, asked whether they trust the national government; 28% said somewhat and more than 40% said not very much or not at all. As practitioners in this field, we understand the importance of building trust and enabling meaningful inter-personal connection as part of the reconciliation journey. South Africa has a long way to go.

I am not a pessimist. In my daily life I also see changes which give me hope that our society is changing. I do however feel strongly that for the benefit of other countries embarking on transitional justice processes we need to look very critically at the South African journey, in order to learn as much from its failings as from its successes.

(Main image: People participate in the opening session of the TRC on 15 April 1996 in East London, South Africa. – Philip Littleton/AFP/Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.